Maybe the only way history becomes meaningful to anyone is when it illuminates your own experience, and vice versa. As a white person who was around for the Civil Rights Movement and played a very small role in it, I thought I understood something about the realities of our bloody history.

There was, of course, the one great peaceful moment: the 1963 March on Washington. I rode down from Boston overnight in the vast cavalcade of buses streaming south to hear Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

The following year, I picketed the Boston School Committee over segregation and was escorted to safety when Southies arrived in force. I was acutely aware of the violence faced by the people my own age who went down to Mississippi for Freedom Summer, from fire hoses and police dogs to murders and bombings. (The guy who pulled me off the Boston picket line had just returned from Mississippi.)

All of which counts for nothing. In fact, I understood very little either of the realities of the black experience in America or of the extent to which the violence of racism has shaped and warped us and our culture. Two excellent, compulsively readable books have made that plain: Ecstatic Nation: Confidence, Crisis, and Compromise, 1848-1877 by Brenda Wineapple (2013),

and The Warmth Of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration by Isabel Wilkerson (2010).

I read the later book first. I’d noted the interesting reviews for The Warmth Of Other Suns, a New York Times best seller and National Book Critics Circle Award winner, but kept putting off buying it since I thought I knew the history, more or less. But while reading Ecstatic Nation (a New York Times Notable Book and a Kirkus Best Book of 2013), I saw that Wilkerson’s book would be essential; I would need to continue the story, because I didn’t really know it at all.

The first thing Wineapple showed me was that the speculation I’d encountered in my reading over the years, as to whether the Civil War was really about slavery or about something else—land, or industrialization, or states’ rights—was all canard. Slavery and race were fundamental, had been since the beginning.

I got bogged down a bit during the Civil War itself, to which I’d had a fair amount of exposure growing up, starting with the fact that my great-grandmother had been a teenager in Gettysburg during the Battle and written a monograph about it, while my grandmother lived there. I spent a fair amount of childhood time tramping around the battlefield while the menfolk rehashed the battle: Big and Little Roundtop, Seminary Hill, the Wheatfield and Pickett’s Charge. (I don’t recall The Emancipation Proclamation ever coming up.)

But when Wineapple got to Reconstruction—the chaotic period after the Civil War when the (non-former-slave-) states ratified, and the federal government attempted to enforce, the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments that abolished slavery and guaranteed citizenship, equal protection under the laws and the right to vote—doors opened in my own history.

At 10, I’d acquired a Baltimore-born-and-bred stepmother, and shortly thereafter taken my first trip South. Waiting at the terminal for what she called the Kiptopeke-Cape Charles ferry that would take us across the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay to Virginia Beach, I saw my first “Colored Only” and “White Only” signs over the water fountains.

I didn’t ask any questions; in my family, that didn’t get you anywhere. I just stored the image away. Next to it I filed the racist jokes to which I was inevitably exposed (and to which I can recall no one on the Northern side of the family objecting); still later, there were those newspaper and TV images of the violence of the Civil Rights era.

Both books made me see, clearly, the long history of that violence. That those signs on the water fountains on that deceptively peaceful summer’s day at the ferry terminal had been a manifestation of its power. I saw what a short time it had been to that day in 1950 from 1876, when the Supreme Court decided that, despite the 14th Amendment, the massacre of 80 free black people quietly exercising their civil rights was not the business of the federal government.

Or even from 1865, when the Civil War ended and large numbers of whites in the South became determined to reestablish, minus only legal enslavement, the status quo ante. It was all the same violence, sustained over the length of a single long lifetime. Someone could have been born in 1865, lived to see those water-fountain signs in 1950, and died believing that nothing had changed, that whites were still supreme.

It was a very short hop from 1950 to 1964 and the lynching of Mississippi Freedom Summer activists Michael Schwerner, Andrew Chaney and James Goodman. But by that time a great deal had changed: The Civil Rights Movement–in which black people were reasserting their rights under those “Reconstruction Amendments”–had gotten underway in the early 50s. Now Northern whites, among them Schwerner and Goodman, were in Mississippi to help black people register to vote.

FBI Poster of Missing Civil Rights Workers James Goodman, Andrew Chaney and Michael Schwerner, Summer 1964

Wineapple shows how the pattern, the tradition of violence that in a way culminated in the lynching of those young civil rights workers, had been established, starting almost immediately after the Civil War and intensifying throughout Reconstruction, as freedmen first began voting and otherwise exercising their rights as citizens.

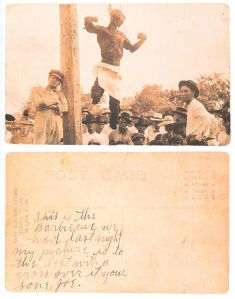

Lynching was mob murder committed with impunity, whether as punishment or just because the lynchers could. Tuskegee Institute, which kept records, required at least three lynchers for a murder to qualify as a lynching. According to its records, 3,445 black people were lynched between 1882 (before which no records were kept) and 1964, most from the 1890s to the 1930s.

Lynching, in other words, became routine, just the ultimate threat designed to keep black people down. The ex-Confederate states also passed “Jim Crow” laws depriving blacks of all the rights granted them under the 14th and 15th Amendments.

I grew up during the Jim Crow era—officially, 1877, when the federal government stopped trying to enforce the Reconstruction Amendments, to 1954, when, in response to suits brought by black people in Brown v. Board of Education, the US Supreme Court desegregated public schools. By the time of my childhood, the whole pattern of violence had become so routine that it was largely invisible to white people in the North.

So, it seems to me, we who grew up white in the North could not and did not comprehend the reality that both books, especially Wilkerson’s, make crystal-clear. It wasn’t just that white people could murder black people, whether for whim or reason, and get away with it. It was that every black person in post-Civil War Confederate territory lived within an impenetrable maze of written and unwritten laws, rules, customs and whims, and that, for the witting or unwitting infraction of any or none of them, he or she could at any moment be murdered. And there was no redress.

If you weren’t physically murdered, you were psychologically murdered, living in essentially the same appalling funk as slaves had. As a young woman, I’d learned something about that from another terrific book, Puttin’ on Ole Massa: the Slave Narratives of Henry Bibb, William Wells Brown, and Solomon Northup, edited by Gilbert Osofsky (1969). Their stories had made me conscious of what, instinctively, seemed to me the central psychological condition of slavery: unremitting fear, terrible confinement, a continual diminishing, rather than expanding, of horizons. The absolute inability to exert free will. Wilkerson shows that the conditions imposed on black people in the Jim Crow South were not much different.

There were all kinds of lynchings, some very public. In 1916, 17-year-old Jesse Washington, illiterate and perhaps “feebleminded”, confessed to the murder of his cotton-farmer-boss’s wife and, after being convicted in court, was burned alive in Waco, Texas before some 15,000 spectators, the event commemorated with photographs circulated as postcards.

But it seems that many, perhaps most, lynchings were secret, anonymous, dead-of-night affairs. And it’s likely that a great many of those were never captured in the official records, which relied largely on newspaper reports. According to the Tuskegee records, after 1935 the number of lynching per year fell to the single digits. In fact, the lynching of Schwerner, Chaney and Goodman seems to have been the last one that Tuskegee recorded.

Certainly the lynchers never intended for that one to become public: the three Civil Rights volunteers, driving in one car, were set up by the local sheriff and Ku Klux Klan, ambushed on a back road in the dead of night, shot (Chaney, for the crime of being black, was first savagely beaten), and buried deep in an earthen dam. Locally, everyone would have known about it; that was how lynching enforced the status quo.

But of course that lynching—which had been undertaken precisely because Freedom Summer was threatening the status quo—did not remain secret. Because Northern whites had likely been killed, and because the Civil Rights Movement was in full flood and there were nationwide protests, the Federal government got involved. The FBI and the military were brought in, and within a few weeks the bodies of the three young men were found. The Klan and the sheriff had merely done what whites had been doing as a matter of course for almost a century (the searchers also found a number of lynched black bodies submerged in various rivers and creeks, some never identified). White supremacists didn’t realize that time was finally catching up with Jim Crow.

President Lyndon B. Johnson meets with Civil Rights leaders Martin Luther King, Jr., Whitney Young, and James Farmer, January 1964.

If we in the North were shocked by the violence of the response to the Civil Rights Movement, then, it was because we didn’t understand the simple fact that it was just business as usual, merely a continuation of the violence that had undermined Reconstruction and enforced Jim Crow—and that had been built into the system of slavery that was, after all, an important underpinning of the agrarian economy of the United States. (Although lynching as such was apparently not so much a feature of slavery, there being many other forms of violence available to slave owners short of destroying their property.)

The history and condition of lynching, both physical and psychological, is the backdrop against which the personal histories in Wilkerson’s book unfold. Black people subjected to Jim Crow had started protesting early, and in what was at the time the only effective way possible: with their feet. Thousands of “Exodusters” had migrated to Kansas as early as 1879. By the early 20th century the Great Migration, Wilkerson’s subject, was on. From 1915 to 1970, six million blacks fled the south. “They did what human beings looking for freedom, throughout history, have often done.” she writes. “They left.”

The great surge in migration started during World War I, for the simple reason that there were jobs in the North. The War had created a shortage of workers in northern factories, and companies sent undercover agents south to recruit blacks. Under Jim Crow, they couldn’t do this openly; they had to infiltrate black communities and, in complete secrecy, spread the news. Once people started leaving, word filtered back (again, in secrecy) and more saw a way out.

Wilkerson tells the story of the Great Migration through the lives of three people, each of whom left a different part of the South in a different decade, and for a different destination determined largely by the route of the railroad line that transported them, or had transported others from their town or region who’d gone before. They were not free to just pick up and leave; the Jim Crow South would go to any lengths to keep its supply of cheap labor. Wilkerson’s account makes escaping from it seem a good deal like escaping from the Soviet Union or East Germany during the Cold War; it required planning, guile, luck and, above all, secrecy.

Two of her three protagonists fled in fear for their lives: In 1937 Mississippi, the sharecropper husband of Ida Mae Brandon Gladney had good reason to believe that he and his wife might be targeted by the same whites who’d beaten a cousin almost to death for allegedly stealing turkeys from George Gladney’s boss. (The birds had merely wandered off.) The Gladneys made it to the Midwest, ultimately to Chicago.

In 1946, George Starling managed, by a roundabout way, to catch the train from Florida to New York, after he’d been warned of a plot to lynch him in retaliation for trying to organize his fellow citrus pickers, who in fear for their own lives had informed on him.

Wilkerson’s third protagonist, Robert Pershing Foster, a surgeon from the small black elite, fled Louisiana for California by car in 1951 to escape what I would call soul murder: the almost total lack of options for exercising his capabilities and developing his potential as a surgeon and human being. In this context, Wilkerson cites a white woman asking, “If these Negroes become doctors and merchants or buy their own farms, what shall we do for servants?”

In the North, the migrants endured segregated housing, job discrimination, and a host of other indignities. But they would not be murdered for trying to vote—in Chicago, Ida Mae found that, “the very party and the very apparatus that was ready to kill them if they tried to vote in the South was searching them out and all but carrying them to the polls.” Their children could get a real education, not be forced to quit school to pick crops.

Wilkerson has been chastised by a New York Times critic for ignoring a book that stresses the negative impact of the Great Migration: “Wilkerson has little to say about the following generation or its problems beyond a cheerful listing of politicians, athletes, musicians, writers and film stars who got the opportunity ‘to grow up free of Jim Crow and to be their fuller selves’ because their parents had joined the Great Migration.”

I’d say he’s missing the point. On the evidence of these two books, had their parents or grandparents failed to migrate North those black politicians, athletes, musicians, writers and film stars, most of them iconic names, would likely simply not have existed as we know them. Wilkerson writes that “it cannot be known what course the lives of” James Baldwin, Aretha Franklin, Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson and many others would have taken. But any black person living under Jim Crow had few or no opportunities to learn, let alone develop to its highest level and practice, his or her art, sport or profession. Instead, we might have had more maids, sharecroppers, lynching victims. And we would all have been impoverished.

Tags: Andrew Chaney, Brenda Wineapple, Civil Rights Movement, Ecstatic Nation, Great Migration, Isabelle Wilkerson, James Goodman, Jim Crow, lynching, lynching records, Michael Schwerner, The Warmth of Other Suns, Tuskegee Institute

July 27, 2014 at 2:40 pm |

As usual, Hammer’s trenchant and thought-provoking insights and observations are much appreciated.